At the church of St Polycarp, on Wisewood Lane, the LEDs have failed in the arms of the wall-mounted cross, leaving a single white vertical beam. There are streetlights and house lights and garden lights the length of Loxley Road. It is more light than I need, more than I can think with. I am walking to the edge of the city. To leave the lights of the city. I am thinking of my great aunt, on and off, my late aunt Jean, I am thinking of her as the traffic dies down, as the gaps between the houses grow. All I have left of her is a small lump of rock from the constellation of Perseus and a handwritten note that has darkened with age. And my memories, brittle, blurred exposures, shelved out of reach, and my mother’s memories, preserved in speech, as stories, always at hand. It seemed that every August we went into the west, as a family, it seemed that we had always done this, I was the youngest, the thrill of climbing into the car in darkness, my father’s bid to beat the tailbacks. We went into the west, further and further, over the Severn, the first light and the first, familiar changes, immediate and indirect, slower, steeper, a different language on the roads, the roads twisting into narrow tracks. At the end of it all is my aunt Jean. She is somewhere between the hay barn and her static caravan, this is how I remember it, her appearance coinciding with our arrival, a wave, a greeting, a few words exchanged as we work out which pitch is ours for the week. There are perhaps six caravans on a slightly uneven grassy strip at the top of a sloping field. The caravans are laid out in two rows, three in the shadows of hedges and trees, three overlooking the land as it falls away. Ours is the middle caravan with a view of the field. There is no one else at the caravans, only my parents, my two brothers, and me. It is 1980, 1981, 1982. I am eight or nine or ten. When it is dark, if the night is clear, I set a deckchair on the grass, a short distance from the caravan, and settle in, blanketed at the legs, binoculars in my lap. I am facing west. My head tilts and turns until my eyes have made the first adjustments. There are perhaps one or two distant points of electric light, a cottage, a farmhouse. A copse to the south. The dark crease of the Preseli mountains. After a few minutes, my gaze shifts to a region between the zenith and the horizon, a broad belt of sky that I can scan sidelong without moving my neck. After a few minutes more, this is all I see. A first faint streak. I am an amateur, I understand this much, the science is beyond me. Half an eyeblink. There is nothing for it but patience, I will learn nothing by keeping count, keeping time. A second faint streak. I cannot read the sky, I cannot place the constellations, but I can grasp a pattern of disturbance. Another streak, a little brighter, a little longer. There is a trick, a feint, to face the dark field without staring into it, to stay focused without a focal point. This is how the Perseids get in, at the edge of eyeshot. There are clusters and peaks and the waiting is more than just watching. East to west in a split second. No warnings. No repeats. I hold my position for an hour, perhaps more, I think that a hundred meteors must have passed through that hour, but I can’t know this and it doesn’t matter. I am cold. I lose my place, or abandon it. My body stretches out and falls back to earth. It is all still there, near and far, taking shape at different speeds. The field as it falls away. The outline of the caravan. The binoculars untouched in my lap.

At the church of St Polycarp, on Wisewood Lane, the LEDs have failed in the arms of the wall-mounted cross, leaving a single white vertical beam. There are streetlights and house lights and garden lights the length of Loxley Road. It is more light than I need, more than I can think with. I am walking to the edge of the city. To leave the lights of the city. I am thinking of my great aunt, on and off, my late aunt Jean, I am thinking of her as the traffic dies down, as the gaps between the houses grow. All I have left of her is a small lump of rock from the constellation of Perseus and a handwritten note that has darkened with age. And my memories, brittle, blurred exposures, shelved out of reach, and my mother’s memories, preserved in speech, as stories, always at hand. It seemed that every August we went into the west, as a family, it seemed that we had always done this, I was the youngest, the thrill of climbing into the car in darkness, my father’s bid to beat the tailbacks. We went into the west, further and further, over the Severn, the first light and the first, familiar changes, immediate and indirect, slower, steeper, a different language on the roads, the roads twisting into narrow tracks. At the end of it all is my aunt Jean. She is somewhere between the hay barn and her static caravan, this is how I remember it, her appearance coinciding with our arrival, a wave, a greeting, a few words exchanged as we work out which pitch is ours for the week. There are perhaps six caravans on a slightly uneven grassy strip at the top of a sloping field. The caravans are laid out in two rows, three in the shadows of hedges and trees, three overlooking the land as it falls away. Ours is the middle caravan with a view of the field. There is no one else at the caravans, only my parents, my two brothers, and me. It is 1980, 1981, 1982. I am eight or nine or ten. When it is dark, if the night is clear, I set a deckchair on the grass, a short distance from the caravan, and settle in, blanketed at the legs, binoculars in my lap. I am facing west. My head tilts and turns until my eyes have made the first adjustments. There are perhaps one or two distant points of electric light, a cottage, a farmhouse. A copse to the south. The dark crease of the Preseli mountains. After a few minutes, my gaze shifts to a region between the zenith and the horizon, a broad belt of sky that I can scan sidelong without moving my neck. After a few minutes more, this is all I see. A first faint streak. I am an amateur, I understand this much, the science is beyond me. Half an eyeblink. There is nothing for it but patience, I will learn nothing by keeping count, keeping time. A second faint streak. I cannot read the sky, I cannot place the constellations, but I can grasp a pattern of disturbance. Another streak, a little brighter, a little longer. There is a trick, a feint, to face the dark field without staring into it, to stay focused without a focal point. This is how the Perseids get in, at the edge of eyeshot. There are clusters and peaks and the waiting is more than just watching. East to west in a split second. No warnings. No repeats. I hold my position for an hour, perhaps more, I think that a hundred meteors must have passed through that hour, but I can’t know this and it doesn’t matter. I am cold. I lose my place, or abandon it. My body stretches out and falls back to earth. It is all still there, near and far, taking shape at different speeds. The field as it falls away. The outline of the caravan. The binoculars untouched in my lap.

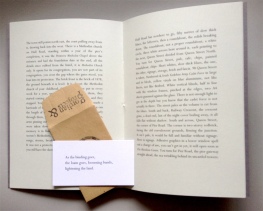

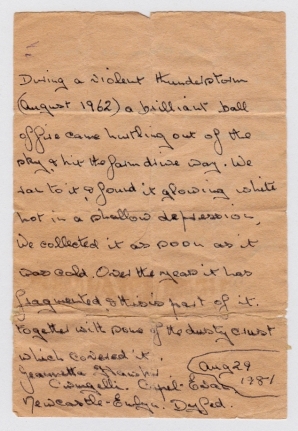

Loxley Road yarns into the west, the north-west, drawn by an incline. I break it down with familiar daymarks, an old garage and its ghost signs, the wide turn for the retirement village, the half-lit profile of a friend’s house. There are stonewalled sections and tree-lined sections and the occasional gap between houses and there is nothing to stop my thoughts from tumbling down the bank to the dark river valley. The Wisewood Inn is closed or closing, I glimpse two people still seated in the rear garden, sharing a joke, an anecdote, trying to find a way to the end of a tale. My aunt Jean was a gifted storyteller, a talent that she nurtured from childhood until the end of her days, but I never heard her story, not from her, and not in her lifetime. I never got it straight, or whole, only the fragments, passed down, pieced together. She was born in 1911, in Purton, Wiltshire, to working-class parents, the eighth of ten children, the ninth was my grandmother, my mother’s mother. She married, had three children, her husband, a good man, became ill, she nursed him, he died. She then took a job driving a milk float to support her family. Jean and the children lived in a council bungalow in Swindon, not far from my grandparents, they were close, supportive, my grandfather supplied her with vegetables he’d grown, she helped with childcare during the school holidays, all the children gathered round for a story. She met the man who became her second husband a few years after the war, the 1950s, even, no-one seems to have the dates. After they married he stopped working and started to fritter her wages on greyhounds. He became abusive, repeatedly, something which was hidden from the family for months or years. One day she disappeared. No-one knew where she was. She left her husband a bed, a chair, a saucepan, a plate, one knife, one fork, one spoon. No note. A few weeks later, my grandmother received a letter. Jean was in west Wales, at a small farm in the hills, a few miles south of Newcastle Emlyn. She had gone there with Derek, a family friend who became her partner, and who had bought the farm. There was a request in the letter, to keep the details from her husband, not to tell him where she’d gone, not to tell him anything. He never saw her again. That must have been the first letter, or one of the first letters, so many letters that radiated from that distant point, no two alike, scatterings of news, poems, riddles, stories, fancies, flights, all in that sloping script, strewn throughout the years. I never saw her anywhere but the farm, not that I remember, and so I grew up thinking that the place had always been part of her, that it was all of her. It never occurred to me to wonder if or when or why she had gone into the west. After forty years with Derek, she left him, and the farm, he had been unfaithful, she wasn’t going to put up with it, so she walked away, near the end of her ninth decade, and settled in a retirement home. He never saw her again. The letters continued. She spent her days reading, and writing, and I sometimes wrote back, but not often enough. The letters petered out and the next thing, the last thing, was a telephone call, to say that she’d died, in her early 90s. It was too late for me to write anything. I thought of the story that she told me when I was a boy, of how, during a violent thunderstorm in August 1962, ‘a brilliant ball of fire came hurtling out of the sky and hit the farm driveway’, where she found it ‘glowing white hot in a shallow depression’. I am thinking of it now, a story passing through her story, speeding up, slowing down. She collected the meteorite as soon as it was cold, and held onto it all that time, even as it fragmented, and gave one of the fragments to me in August 1981, a small lump of rock from the constellation of Perseus, and the story of its journey, a handwritten note that has darkened with age, that I have held onto all this time.

Loxley Road yarns into the west, the north-west, drawn by an incline. I break it down with familiar daymarks, an old garage and its ghost signs, the wide turn for the retirement village, the half-lit profile of a friend’s house. There are stonewalled sections and tree-lined sections and the occasional gap between houses and there is nothing to stop my thoughts from tumbling down the bank to the dark river valley. The Wisewood Inn is closed or closing, I glimpse two people still seated in the rear garden, sharing a joke, an anecdote, trying to find a way to the end of a tale. My aunt Jean was a gifted storyteller, a talent that she nurtured from childhood until the end of her days, but I never heard her story, not from her, and not in her lifetime. I never got it straight, or whole, only the fragments, passed down, pieced together. She was born in 1911, in Purton, Wiltshire, to working-class parents, the eighth of ten children, the ninth was my grandmother, my mother’s mother. She married, had three children, her husband, a good man, became ill, she nursed him, he died. She then took a job driving a milk float to support her family. Jean and the children lived in a council bungalow in Swindon, not far from my grandparents, they were close, supportive, my grandfather supplied her with vegetables he’d grown, she helped with childcare during the school holidays, all the children gathered round for a story. She met the man who became her second husband a few years after the war, the 1950s, even, no-one seems to have the dates. After they married he stopped working and started to fritter her wages on greyhounds. He became abusive, repeatedly, something which was hidden from the family for months or years. One day she disappeared. No-one knew where she was. She left her husband a bed, a chair, a saucepan, a plate, one knife, one fork, one spoon. No note. A few weeks later, my grandmother received a letter. Jean was in west Wales, at a small farm in the hills, a few miles south of Newcastle Emlyn. She had gone there with Derek, a family friend who became her partner, and who had bought the farm. There was a request in the letter, to keep the details from her husband, not to tell him where she’d gone, not to tell him anything. He never saw her again. That must have been the first letter, or one of the first letters, so many letters that radiated from that distant point, no two alike, scatterings of news, poems, riddles, stories, fancies, flights, all in that sloping script, strewn throughout the years. I never saw her anywhere but the farm, not that I remember, and so I grew up thinking that the place had always been part of her, that it was all of her. It never occurred to me to wonder if or when or why she had gone into the west. After forty years with Derek, she left him, and the farm, he had been unfaithful, she wasn’t going to put up with it, so she walked away, near the end of her ninth decade, and settled in a retirement home. He never saw her again. The letters continued. She spent her days reading, and writing, and I sometimes wrote back, but not often enough. The letters petered out and the next thing, the last thing, was a telephone call, to say that she’d died, in her early 90s. It was too late for me to write anything. I thought of the story that she told me when I was a boy, of how, during a violent thunderstorm in August 1962, ‘a brilliant ball of fire came hurtling out of the sky and hit the farm driveway’, where she found it ‘glowing white hot in a shallow depression’. I am thinking of it now, a story passing through her story, speeding up, slowing down. She collected the meteorite as soon as it was cold, and held onto it all that time, even as it fragmented, and gave one of the fragments to me in August 1981, a small lump of rock from the constellation of Perseus, and the story of its journey, a handwritten note that has darkened with age, that I have held onto all this time.

Black Lane on my left, a right angle with Loxley Road. Rodney Hill ahead on my right, an acute angle on a steep slope. The houses stop dead at the lane, lowlit fields unroll to the river, white glint of paddock posts, no movement. Then a small cluster of detached properties, either side of the gates to Wisewood Cemetery. I know it from the south, from walks along Black Lane, it is disquieting, the cemetery, its position is disquieting, exposed on all sides, laid out on a geometric plan. I pass the last detached house on my left and I try to forget about the cemetery. The pastures skew into the south, the road resets from west to north-west, rising on the turn. I wait until I am halfway between one lamp and the next and I look out across the valley and then above the valley and for a second all I see is coal-dark seams between the copper clouds. Then I look back at the road and I lose the impression. I remember the chain of lights that stretches to the reservoir, it stretches ahead of me now, blinding the sky, and I remember that the road to the reservoir is straight, unimpeded, I can see the lights of a car turning east from Storrs Bridge Lane, half a mile or more, and the distance is flooded, and the flood is closing in. I wait until the car is a few hundred metres off and then blinker my eyes with my right hand and hold it there until the car has passed and then drop it as the flood recedes. I do this over and again as I walk into the west. I have my seven-year-old self for company, six or seven or eight, kneeling on my bedroom floor, next to my mother, who has woken me, and herself, from sleep at 2am, because I asked her to, because it is the Perseids, it is my first year of Perseids. We wait at my bedroom window, facing north-east, how dark it is, in memory, we wait and nothing happens. Something shifts, some small adjustment, and we start to say what we think we’ve seen, did you see that, no, or yes, and the doubts are set aside, and my mother sees what I see, and I see what she sees. The road climbs again, the turn for Lea Bank Nurseries briefly lit by a passing car, Storrs Bridge Lane still somewhere ahead. Here I am in West Sussex, with Emma, August 2013, flat on our backs at the edge of a village, looking up, facing east. Her first year of Perseids, my first year for a decade or more, did we mean to do this, is it an afterthought. We are housesitting for my brother. I think that the shower has already peaked and that we will be lucky to see anything. We step out just after midnight and spread our blankets on the common ground at the end of the lane. Emma sees them first. After that they don’t stop. The road descends by increments, one or two or three percent, and I realise that the lamps are out, that there are no lamps on this part of the road, there never have been, and this is not how I remember it. On my left, a thicket of trees, a turn that I don’t see until it is almost gone, there is just enough light to read Storrs Bridge Lane. It’s four years since I last came this way by night. I stopped a few miles south of Wigtwizzle, then climbed over a fence and propped myself against a north-facing dry stone wall, overdressed, burning up, my back to the gibbous moon. I recall Perseids but nothing else. I fell asleep towards 2am and woke up in the cold of 3am. Then I walked back to Hillsborough, a few sparks here and there, between moonlight and dawn light and the ambient overspill from the east. A dip in the road, a glare in the near distance, something breaking off from it, a car, is it turning, reversing, which way is it going. It speeds towards the city and I squint my eyes as it passes. What’s left are streetlamps, a house, a pub. The Nags Head Inn is closed or closing, a few cars left in the car park, a few people, patrons or staff, gathered near the entrance. A red telephone box marks the turning for Stacey Bank. Two more houses, two more streetlamps, and the night is itself again. The road lifts and bends and dips. I would have been facing east, not west, on those nights in the Welsh hills, and the hills that I looked out on were not the Preseli mountains. I would have been looking out toward Pencader, where Jean would spend her last years, her last days. All this time I have been facing the wrong way. I cross the walled, wooded junction that divides Loxley Road from New Road, the junction that marks the eastern end of Damflask Reservoir, the long dark drop either side of the dam. I walk along Loxley Road for another hundred metres and find the gap in the stone wall that leads to the reservoir path. The path is unlit, twisting and uneven, tree roots breaking through, canopy extending its shadow. I try to navigate by touch. The road is perhaps 50 metres behind me but there is almost no light or noise leaking through. After a few hundred metres I come to the beached boats of the sailing club and a small bench overlooking the water. I sit on the bench. It is a little after 11.30pm. I am facing west, south and west. There are bands of cirrus above the horizon so I stop trying to look at the sky and listen to the reservoir instead. I hear an owl and a moorhen and one or two fish rippling the surface. I cannot place the sounds, so close, so distant. Between the sounds there is a sharp stillness. I look up, there is movement, a satellite, and another, this continues, there are more than I expected. 11.48pm. The cirrus disperses to the west, south and west. 11.51pm. Where did I get the idea that to look west is to look back. 11.54pm. Another satellite. 11.59pm. The stars that I couldn’t join up. 12.03am. A bank of cloud rises from the south and consumes everything. 12.08am. To see the whole sky sideways and no part in particular. 12.15am. The cloud clears. 12.19am. Something in, or out of, the corner of my eye, something that I don’t quite catch.

Black Lane on my left, a right angle with Loxley Road. Rodney Hill ahead on my right, an acute angle on a steep slope. The houses stop dead at the lane, lowlit fields unroll to the river, white glint of paddock posts, no movement. Then a small cluster of detached properties, either side of the gates to Wisewood Cemetery. I know it from the south, from walks along Black Lane, it is disquieting, the cemetery, its position is disquieting, exposed on all sides, laid out on a geometric plan. I pass the last detached house on my left and I try to forget about the cemetery. The pastures skew into the south, the road resets from west to north-west, rising on the turn. I wait until I am halfway between one lamp and the next and I look out across the valley and then above the valley and for a second all I see is coal-dark seams between the copper clouds. Then I look back at the road and I lose the impression. I remember the chain of lights that stretches to the reservoir, it stretches ahead of me now, blinding the sky, and I remember that the road to the reservoir is straight, unimpeded, I can see the lights of a car turning east from Storrs Bridge Lane, half a mile or more, and the distance is flooded, and the flood is closing in. I wait until the car is a few hundred metres off and then blinker my eyes with my right hand and hold it there until the car has passed and then drop it as the flood recedes. I do this over and again as I walk into the west. I have my seven-year-old self for company, six or seven or eight, kneeling on my bedroom floor, next to my mother, who has woken me, and herself, from sleep at 2am, because I asked her to, because it is the Perseids, it is my first year of Perseids. We wait at my bedroom window, facing north-east, how dark it is, in memory, we wait and nothing happens. Something shifts, some small adjustment, and we start to say what we think we’ve seen, did you see that, no, or yes, and the doubts are set aside, and my mother sees what I see, and I see what she sees. The road climbs again, the turn for Lea Bank Nurseries briefly lit by a passing car, Storrs Bridge Lane still somewhere ahead. Here I am in West Sussex, with Emma, August 2013, flat on our backs at the edge of a village, looking up, facing east. Her first year of Perseids, my first year for a decade or more, did we mean to do this, is it an afterthought. We are housesitting for my brother. I think that the shower has already peaked and that we will be lucky to see anything. We step out just after midnight and spread our blankets on the common ground at the end of the lane. Emma sees them first. After that they don’t stop. The road descends by increments, one or two or three percent, and I realise that the lamps are out, that there are no lamps on this part of the road, there never have been, and this is not how I remember it. On my left, a thicket of trees, a turn that I don’t see until it is almost gone, there is just enough light to read Storrs Bridge Lane. It’s four years since I last came this way by night. I stopped a few miles south of Wigtwizzle, then climbed over a fence and propped myself against a north-facing dry stone wall, overdressed, burning up, my back to the gibbous moon. I recall Perseids but nothing else. I fell asleep towards 2am and woke up in the cold of 3am. Then I walked back to Hillsborough, a few sparks here and there, between moonlight and dawn light and the ambient overspill from the east. A dip in the road, a glare in the near distance, something breaking off from it, a car, is it turning, reversing, which way is it going. It speeds towards the city and I squint my eyes as it passes. What’s left are streetlamps, a house, a pub. The Nags Head Inn is closed or closing, a few cars left in the car park, a few people, patrons or staff, gathered near the entrance. A red telephone box marks the turning for Stacey Bank. Two more houses, two more streetlamps, and the night is itself again. The road lifts and bends and dips. I would have been facing east, not west, on those nights in the Welsh hills, and the hills that I looked out on were not the Preseli mountains. I would have been looking out toward Pencader, where Jean would spend her last years, her last days. All this time I have been facing the wrong way. I cross the walled, wooded junction that divides Loxley Road from New Road, the junction that marks the eastern end of Damflask Reservoir, the long dark drop either side of the dam. I walk along Loxley Road for another hundred metres and find the gap in the stone wall that leads to the reservoir path. The path is unlit, twisting and uneven, tree roots breaking through, canopy extending its shadow. I try to navigate by touch. The road is perhaps 50 metres behind me but there is almost no light or noise leaking through. After a few hundred metres I come to the beached boats of the sailing club and a small bench overlooking the water. I sit on the bench. It is a little after 11.30pm. I am facing west, south and west. There are bands of cirrus above the horizon so I stop trying to look at the sky and listen to the reservoir instead. I hear an owl and a moorhen and one or two fish rippling the surface. I cannot place the sounds, so close, so distant. Between the sounds there is a sharp stillness. I look up, there is movement, a satellite, and another, this continues, there are more than I expected. 11.48pm. The cirrus disperses to the west, south and west. 11.51pm. Where did I get the idea that to look west is to look back. 11.54pm. Another satellite. 11.59pm. The stars that I couldn’t join up. 12.03am. A bank of cloud rises from the south and consumes everything. 12.08am. To see the whole sky sideways and no part in particular. 12.15am. The cloud clears. 12.19am. Something in, or out of, the corner of my eye, something that I don’t quite catch.

Sheffield, 12 August 2021 / 24 August 2021

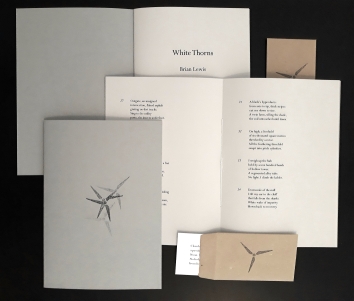

White Thorns is the second pamphlet by Brian Lewis (following

White Thorns is the second pamphlet by Brian Lewis (following